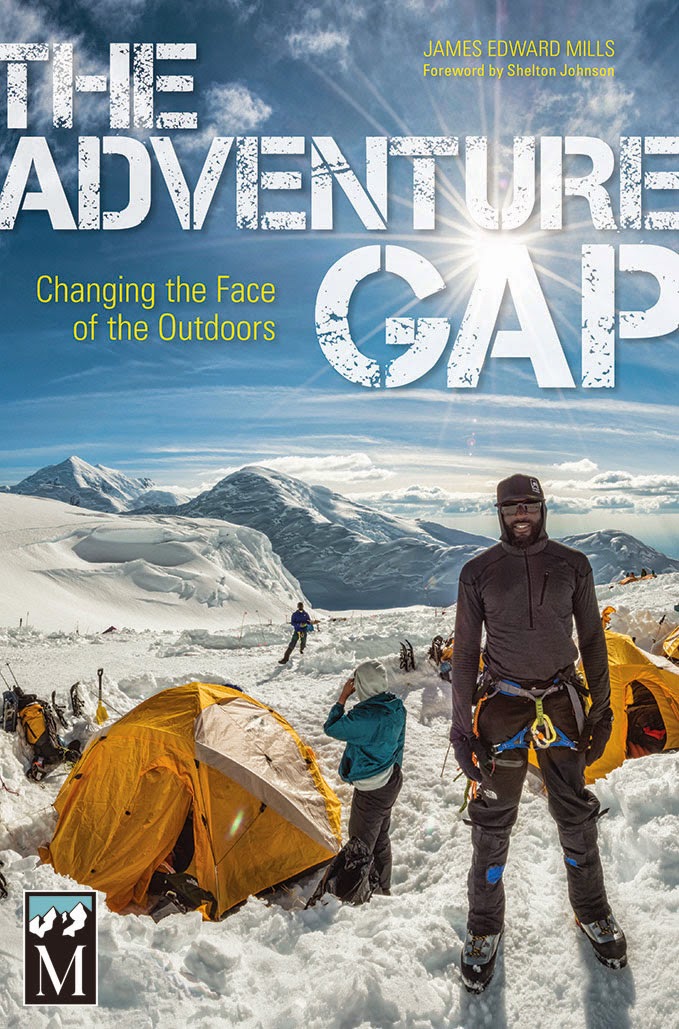

It's no secret that the bulk of those who participate in outdoor adventure sports are caucasian. And while most of us know a few minorities that participate in climbing and skiing, the percentage of those who participate in these sports are miniscule... There just aren't that many minorities playing in the mountains. And that's where James Edward Mills starts in his excellent book, The Adventure Gap.

In 2013 a group of African Americans set out to be the first all black Denali summit team. Their expedition was aptly named, Expedition Denali.

At 20, 320 feet above sea level, Denali, also called Mount McKinley, is the loftiest perch in the United States. As one of the so-called Seven Summits -- the tallest peak on each continent -- Denali is a much-valued prize on most climbers' bucket lists. Both physically and metaphorically: if you can succeed on Denali, you can likely succeed anywhere.

By summiting this high mountain, the members of the Expedition Denali team wanted to show that people of color -- African Americans in particular -- do in fact have a place in outdoor recreation. The objective was to inspire a new generation of minority youth to seek out and enjoy a relationship with the natural world where they might come to play, pursue career opportunities, and fight for its long-term preservation. Like most climbing expeditions the summit was not the sole goal. And for this expedition in particular, the ascent to the summit would be only the first step. The journey would continue for climbers back home in their communities, where each team member would be responsible for sharing their experience and offering encouragement to those around them who aspire to a life of adventure.

The expedition was composed of a number of people from different backgrounds. Some of those on the trip had significantly more mountain experience than others. But they all were aware that putting together a team of African Americans for a Denali climb was something different, something that had not been done before.

A point aptly made in the book's narrative is that the opportunity for people of color to participate in mountain sports often simply isn't there. Perhaps the best anecdote in the book revolves around a young climber on the team by the name of Erica Wynn. The story picks up as she pokes around in a library full of mountaineering books.

As she perused the volumes before her, Erica was reminded that many of these stories were dominated almost exclusively by the adventures and exploits of white men.

Young people are exposed to many narratives, and Erica felt strongly that these stories shape our expectations of ourselves and of our lives. It's problematic if we're exposed to a single story and we can't identify ourselves in that story. Like so many young children, Erica had grown up in a culture heavily influenced by Disney movies and found herself unable to relate to the characters in those stories. The white woman in those movies always gets the happy ending and she rides off with her Prince Charming, she thought. Where is my place? My happy ending?

Erica thought of what little black girls would make of the mountaineering stories like those in the library. They'd think they didn't have a place, or that the odds were stacked against them. She knew that Expedition Denali could help change that. It could add a new story and in that way, help women identify themselves in the outdoors in a way they were unable to in the past.

Racial minorities aren't the only ones that have dealt with this perception. Certainly women have dealt with this as well, but female climbers and outdoor adventurers have made great strides in this arena. And where young women had only few outdoor role models thirty years ago, now they have dozens upon dozens of female sponsored athletes and guides to look up to...

Obviously one expedition is unlikely to change an embedded preconception of who gets to go into the mountains. But every change in perception has to start somewhere. Programs like the one set up to put together Expedition Denali are a great start, but they are just a start. All of us have to be more accommodating to opening up access to the outdoors and to adventure sports for those who don't look like us. It just takes a few programs like this in order to start a trend that might change things; and then perhaps in a few years, there will be a lot of people of color who will be role models for young minority aspiring outdoor adventurers...

Some might say, "but the places where I play are already crowded. I don't want more people there. I want less." This is a valid point, and as an advocate for solitude in the wilderness I hear you...but this is important. It's bigger than our own personal desire to be alone. This issue matters...

The question some may ask is, why does this matter? Mills does an excellent job of answering that question:

African American comprise only a small percentage of people who routinely spend time in nature. Low rates of participation among people of color in adventure sports such as backpacking, rock climbing, downhill skiing, and mountaineering suggest troubling prospects for the future. Very few blacks join environmental protection groups such as the Sierra Club or The Wilderness Society. And an even smaller number can be counted among the corps of professionals in careers dedicated to the preservation and conservation of nature, including national park rangers, foresters or environmental scientists.

It's estimated that by 2042, the majority of US citizens will be nonwhite. Which begs the question: What happens when a majority of the population has neither the affinity for, nor a relationship with the natural world? At the very least, it becomes less likely that future generations will advocate for legislation or federal funding to protect wild places, or seek out job prospects that seek to protect it.

What happens indeed? It seems to me that Mills has thrown down the gauntlet for those of us who love the wilderness. How will we promote outdoor adventure to people of color? How can we get more diverse people into the mountains? How can we protect the future of the lands that we love...?

--Jason D. Martin

No comments:

Post a Comment